Download these actions as a PDF:

Looking for actions for CB-NSG members?

Children, young people and adults will be supported to exercise their human rights (which are the same as everyone else’s) to be healthy, full and valued members of their community with respect for their culture, ethnic origin, religion, age, gender, sexuality and disability – Challenging Behaviour Charter

What actions need to be taken?

1. Bring together different sources of data to improve monitoring and safeguarding

Reporting complaints, allegations, and concerns with services is one of the key ways of identifying safeguarding issues and abuse of people with a learning disability. However, there are currently a number of routes for reporting these. For example, they can be raised with the service directly; reported to the CQC; brought to the local authority; or taken to the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman, among others.

Because these reports can be made to multiple places, it is difficult to capture a full picture of any concerns raised about a service. This could potentially result in issues being missed or dismissed, or an inability to identify patterns of concern due to not having all the data.

We recommend the establishment of a central database that can collect complaints, allegations and concerns from different sources, and which can then be used to monitor services. We believe that this would improve safeguarding and should help identify any issues/abuses at an earlier stage.

This recommendation builds on a similar recommendation made in Professor Glynis Murphy’s second independent report on CQC’s inspections and regulation of Whorlton Hall, and also reflects the findings of ‘Safeguarding Children with Disabilities and Complex Health Needs in Residential Settings’, which was produced following the abuse of 108 children at residential settings operated by the Hesley Group.

The Department of Health and Social Care needs to:

Establish a central database that can collect complaints, allegations and concerns from different sources, bringing them together so that they can be monitored and analysed and so that any patterns can be identified

This is likely to require the involvement of the Department for Education, NHS England, Ofsted, and CQC, among others

2. Stopping the use of harmful restraint

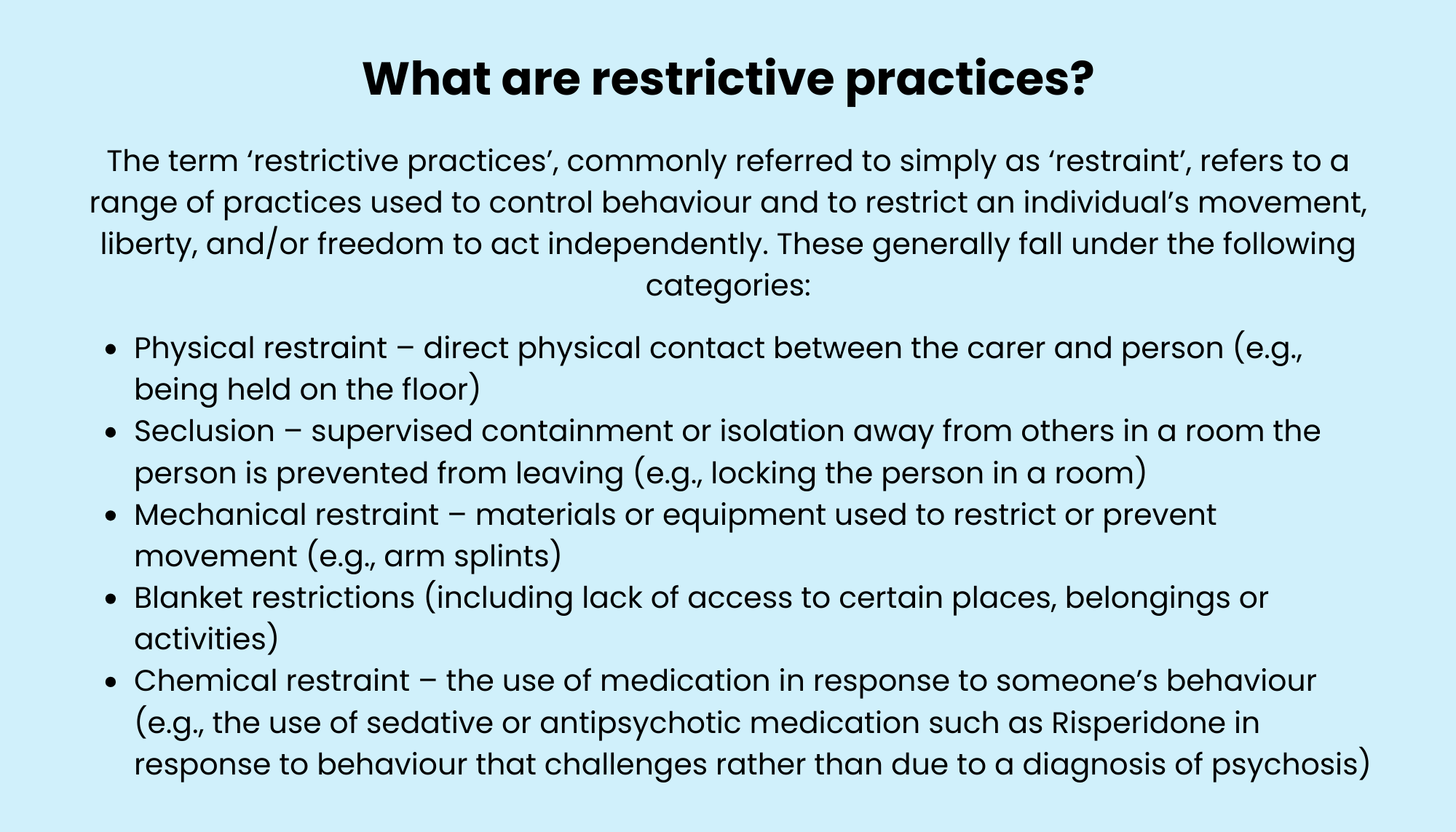

Children, young people and adults with a learning disability, particularly those whose behaviour challenges, are frequently subjected to a range of restrictive interventions in order to control their behaviour. These interventions, including restraint, overmedication, and seclusion, are widespread and cause serious harm and trauma.

In 2023, Baroness Sheila Hollins, an Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry of Learning Disability, published her report on the use of long-term seclusion – described in her report as solitary confinement – in inpatient hospitals for people with a learning disability and autistic people. The report confirmed that this had no therapeutic benefit, and instead caused serious harm and trauma.

This report backs up years of research that has found that children, young people, and adults are subjected to restrictive practices when they are unnecessary, and have experienced significant harm as a result of this. CQC’s ‘Out of Sight’ report, published in 2020, details the human rights abuses that people with a learning disability and autistic people, as well as people with mental health conditions, face in mental health hospitals. Progress reports, published in 2021 and 2022, found that little had changed.

These restrictive practices are not only used in inpatient hospitals – they are also prevalent in schools. Research by the Challenging Behaviour Foundation and Positive and Active Behaviour Support Scotland, with additional analysis by the University of Warwick, surveyed 204 family carers and drew on an additional 566 case studies. This work identified that the use of restrictive practices against children with learning disabilities is widespread and causes physical and emotional harm. Over half of these cases included children between the ages of five and ten – the youngest child identified by this study as having experienced physical restraint and/or seclusion was two years old.

There is currently government guidance on the use of restrictive interventions against children and young people, but the evidence of this study – and many others – show that this guidance is failing for protect children and young people or to uphold their rights. While there is a commitment to update this guidance, and a consultation has been held, there is not yet a date for when this will be published.

In August 2024, the government committed to bringing Section 93a of the Education and Inspections Act 2006 into force from September 2025. This section, which mandates the recording and reporting of incidents of restrictive practice, is a positive step forward. However, it is not enough to require restraint to be recorded and reported – there must also be a focus on promoting person-centred approaches so that children, young people and adults are supported in the least restrictive way possible.

The Department for Education needs to:

Ensure families are informed when restraint is used on their child

Introduce national training standards on use of force, restraint and other restrictive interventions in schools

The Department for Education and the Department of Health and Social Care need to:

Ensure that all guidance clearly defines restrictive practices

Clearly outline alternatives to restrictive practices, and support the implementation of these alternatives

We have worked to co-produce these actions and asks, building on years of work that has gone before it. We are happy to engage with policy makers at a local, regional, and national level about how we can get things right for people with a learning disability whose behaviour challenges. If you would like to talk about any of the actions in this plan, or any work you are planning on doing, please email actionplan@thecbf.org.uk